Tres imágenes cuentan el viaje de este migrante nepalés, que atravesó 15 fronteras para llegar a los EE.UU.

Para muchos migrantes, Puente América, fue el último paso antes del infierno. Esta aldea de 30 casas en Chocó, la provincia más pobre de Colombia, está a menos de 25 kilómetros de la frontera con Panamá si se dibuja una línea recta entre los dos puntos en el mapa. Sin embargo, no existen carreteras rectas en esta espesa selva.

Por lo general, a los viajeros que buscan una vida mejor en los países del norte de América no se les permite ir por medios de transporte regulares de Colombia a Panamá (aunque los hay, desde vuelos directos, lanchas rápidas, hasta senderos ecológicos).

Así que se ven obligados a tomar caminos peligrosos a través de la selva, como el que pasa por Puente América. Llegar a este pueblito es de por sí difícil, pero después, a los viajeros aún les faltan los peores días de camino. A veces van en lanchas rápidas por entre los manglares y, otras, van caminando por senderos resbalosos, para llegar a Juradó, un pueblo más grande en la Costa Pacífica de Colombia, y luego otra vez, toman una lancha para navegar por el río hasta Panamá hasta arribar al pueblo de Yaviza, donde empieza la carretera pavimentada que conecta con Ciudad de Panamá.

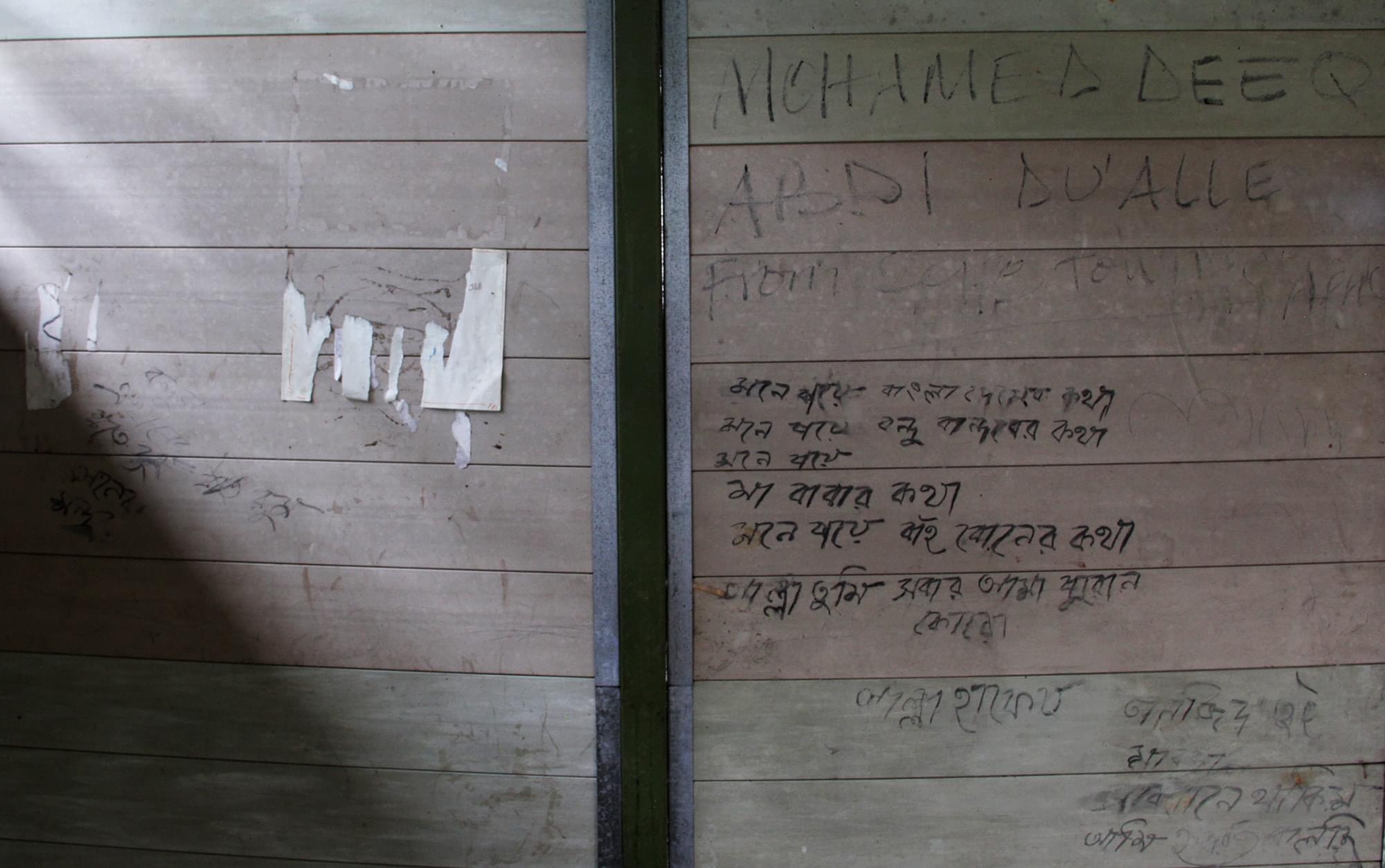

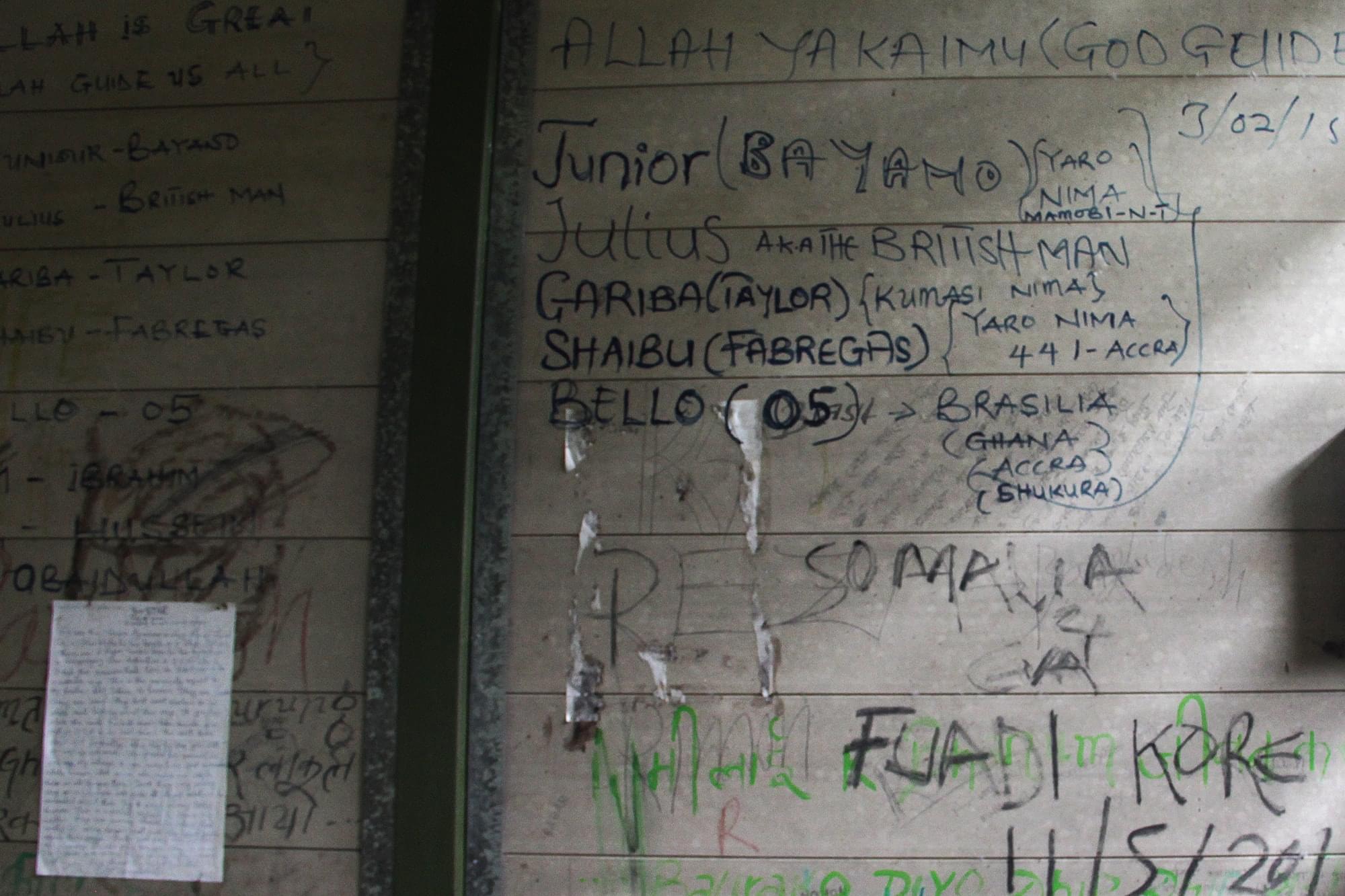

La escuela de Puente América, una ruina vacía hecha de grandes tablones de madera, se ha convertido en un refugio improvisado, donde muchos migrantes pasan una noche en su desalentador viaje. En 2015, un periodista colombiano, José Guarnizo, quien también participó en esta alianza periodística, viajó a Puente América, siguiendo el camino de los migrantes. Encontró firmas y saludos dejados por ellos en las frágiles paredes, como una Torre de Babel. Había mensajes escritos en hindi, inglés, nepalí, francés, bengalí y árabe, algunos de ellos con una fecha o un año junto a un nombre.

“Estuve aquí Ahmed Salah, etíope”. “Alhaji Abass de Mamobi”. “Bilal Warrakh, Pakistán”. “Zakari Ganiou le Beninois”. “Amo Bangladesh”. “Que Alá todopoderoso nos guíe”. “Vamos a USA”.

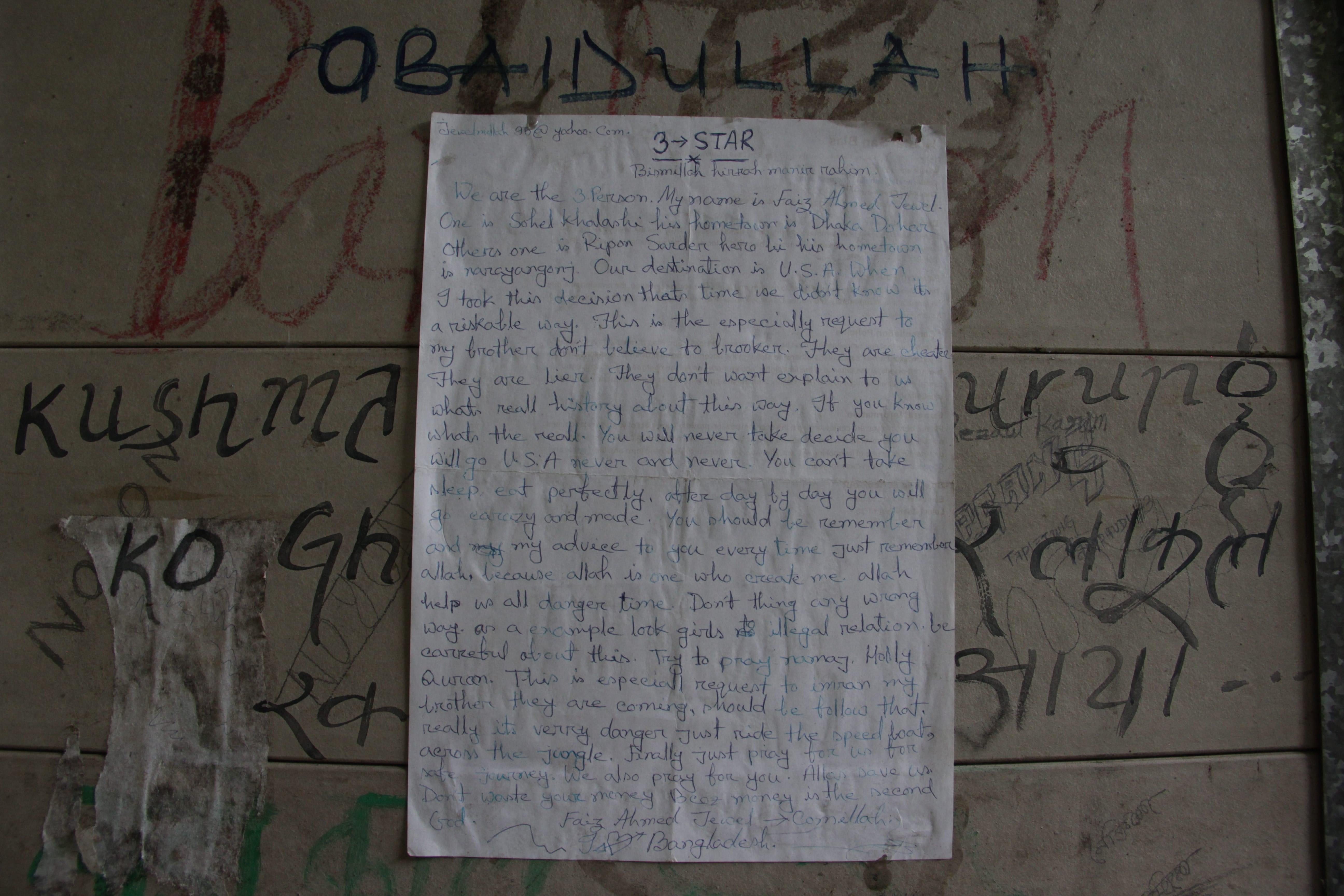

Faiz Almed Jewel, de Daca, Bangladesh, quien explicó que viajaba con otros dos compatriotas, dejó, pegado en la pared, un mensaje escrito a mano en el inglés básico que se podía comunicar:

"Nuestro destino es USA. Cuando tomé esta decisión aquella vez, no sabía que era un vía arriesgada. Esta es la petición especial a mi hermano: no creas en los intermediarios. Son tramposos, son mentirosos. No quieren explicarnos la verdadera historia de esta vía (...) deberías recordar mi consejo cada vez. Sólo recuerda a Alá (...) Intenta rezar el Santo Corán. Esta petición especial para advertir a mi hermano (...) realmente es muy peligroso montar los botes de velocidad a través de la selva. Finalmente, sólo reza por nosotros para un viaje seguro. También rezamos por ti. Que Alá nos salve. No malgastes tu dinero..."

La alianza periodística transfronteriza de Occrp, el Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) y otros 16 medios de comunicación, que produjo la investigación conjunta Migrantes de Otro Mundo, se propuso averiguar qué había sucedido con estos migrantes que habían pasado por el peligroso camino. Durante meses intentamos sin éxito buscarlos.

En 2019, el Occrp se puso en contacto con el periodista independiente nepalí, Deepak Adhikari, para que nos ayudara en la búsqueda. Pudo encontrar a un emigrante nepalí que escribió su nombre en la escuela de Puerto América, con el año 2015 al lado.

No revelamos el verdadero nombre del migrante, ya que prefirió no ser entrevistado, porque teme que pueda obstaculizar su proceso de inmigración en los Estados Unidos. Pero entrevistamos a su familia, algunos amigos y gente que conoce bien la vida del pueblo nepalí donde vivió.

Aquí está su historia.

1. 2014: Kushma, Parbat, provincia de Gandaki, Nepal

En la primavera de 2011, cuando Ramesh Pradhan, entonces de 28 años, se casó con una joven, esperaba que el vínculo durara toda la vida. Había regresado a su casa en Kushma, una pequeña ciudad enclavada en las ondulantes colinas de la provincia nepalí de Gandaki, después de cinco años como trabajador migrante en Corea del Sur. Cinco de sus amigos condujeron más de 150 kilómetros en sus motocicletas hasta Narayangadh para asistir a la ceremonia de la boda.

Pero en menos de un año, su matrimonio comenzó a deshacerse. "Los dos se separaron de manera amarga y abrupta", recuerda Binod Pokharel, un amigo. Antes de casarse, Pradhan había construido una casa de cemento y hormigón cerca del cruce principal de la ciudad.

Levantó la casa en un terreno que recibió de su padre, que se casó con otra mujer y está viviendo con ella en Katmandú. Le costó 1,2 millones de rupias (US$15.800).

Mientras Pradhan se establecía en su casa, docenas de jóvenes se fueron de esta ciudad bendecida por los ríos gemelos Modi y Kaligandaki.

No se dispone de cifras oficiales sobre los emigrantes que salieron hacia Estados Unidos, pero se dispararon entre 2012 y 2015, según un trabajador social local, quien pidió no se le identificara ya que su trabajo podría verse obstaculizado y quien conoce el tema bien. En un barrio de Kushma, 27 hombres de unas ocho familias han hecho el viaje a Estados Unidos.

Los datos de la Patrulla Fronteriza de los Estados Unidos muestran que entre 2014 y 2019, 5 200 nepalíes fueron aprehendidos en el país, casi todos en la frontera sur.

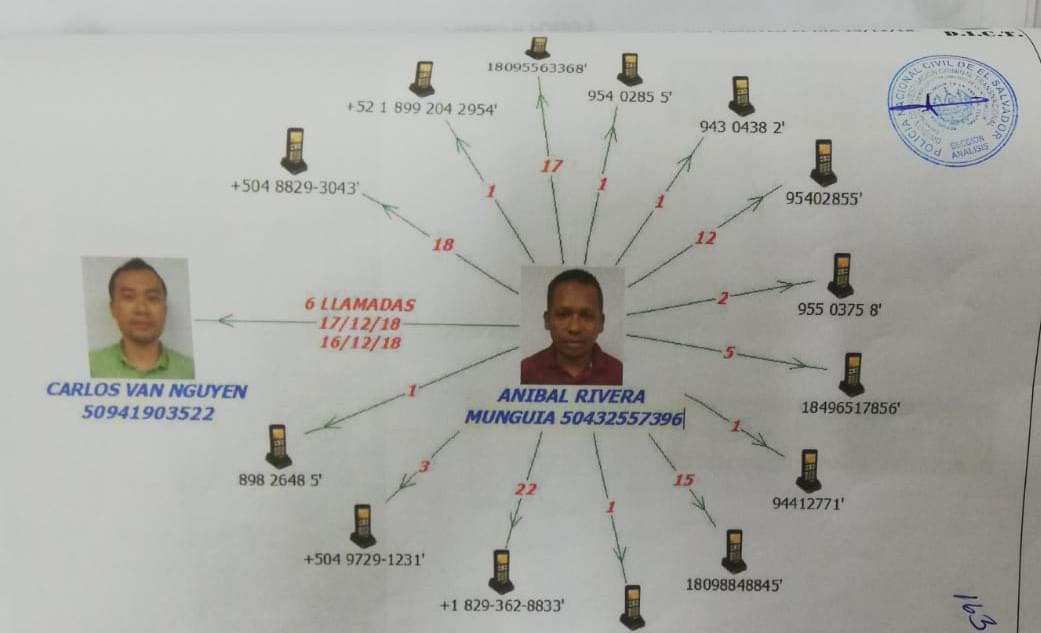

Alrededor de 500 migrantes han emigrado a Estados Unidos desde Kushma, dijo el trabajador social. "Alrededor de 8-10 traficantes operan aquí. Cada uno de ellos ha traficado con migrantes, desde transportar a unas pocas decenas, hasta llevar a 200", dijo. Mientras que los jefes de las redes de tráfico viven en Katmandú y Nueva Delhi, los traficantes locales, que forman parte de las redes internacionales, explotan sus conexiones y la confianza que puedan tener en ellos los posibles migrantes.

"En primer lugar, es una sociedad muy cerrada y, en segundo lugar, los traficantes pueden haber enviado a uno de sus familiares a los Estados Unidos”, dijo la trabajadora social. "Así que todo se mantiene en secreto, a pesar de estar tan extendido".

Sólo una persona, Raju Paudel, que dirigía el Instituto de Informática y Multiservicios Manakamana en Kushma, ha sido condenado hasta ahora por delitos relacionados con tráfico de migrantes. El 17 de junio de 2019, el Tribunal de Distrito de Parbat encarceló a este hombre de 39 años durante un año y le impuso una multa de 10 000 rupias nepalesas (88 dólares).

Kushma tiene alrededor de 12 000 habitantes, pero alberga un gran número de instituciones financieras, entre las que se encuentran nueve bancos comerciales privados, tres bancos estatales, 250 cooperativas, cinco bancos de desarrollo y tres empresas de inversión. También hay sistemas informales de crédito y ahorro como el Dhukuti.

El sistema financiero no regulado o escasamente regulado es utilizado tanto por los traficantes como por las familias de los migrantes. Los migrantes recurren a ellos para obtener crédito y viajar.

El sistema financiero no regulado o escasamente regulado es utilizado tanto por los traficantes como por las familias de los migrantes. Los migrantes recurren a ellos para obtener crédito y viajar.

Parbat no es el único distrito con un gran número de migrantes que toman la arriesgada ruta localmente llamada Tallo Bato (literalmente “por el camino”, pero es más exacto traducirlo “la ruta de sur a norte”). En una docena de distritos en la región centro-occidental de Nepal hay contrabando de personas hacia Estados Unidos.

Oficiales de policía en la capital Katmandú dijeron que actualmente hay 5 000 nepalíes en camino hacia ese país. "Hemos llegado a esta cifra basándonos en nuestras investigaciones, incluyendo el testimonio de los migrantes que han sido deportados desde Estados Unidos, los traficantes que hemos arrestado, entre otros", dijo Ishwar Babu Karki, jefe de la Unidad Anti-Tráfico de la Policía de Nepal.

Su colega, Narahari Regmi, superintendente adjunto de la policía, calificó el tráfico de personas como uno de los delitos más graves que enfrenta Nepal. "Debido al tráfico, las aerolíneas internacionales a veces se niegan a abordar a un nepalí en sus aviones. Hemos pagado un alto precio por el contrabando de personas", dijo.

Sentada en las escaleras de la casa que Pradhan construyó antes de su viaje a Estados Unidos, Mithu Pradhan, su madre, dijo que su hijo se inspiró en los amigos que se fueron antes que él. "Uno por uno, sus amigos se fueron a América. Regresaron con dinero. Creo que él quería seguir sus pasos", dijo la mujer de 69 años.

"Me decía que tenía grandes sueños y que quería ir a grandes países", dijo. "Pase lo que pase, quiero llegar a América", recordó que le decía. "Era una cuestión de vida o muerte, pero no podía impedírselo”.

El matrimonio fallido, la falta de empleo y su deseo de ganar dinero parecieron haber llevado al joven a su viaje, dijeron sus amigos y familiares. "Tenía un estilo de vida caro. Solía salir de fiesta o salir de paseo", dijo su amigo Pokharel, dueño de una joyería en Kushma. Shrestha, su primo, estuvo de acuerdo: "Sus gastos eran muy altos, pero no tenía ninguna fuente de ingresos. Así que decidió ir a Estados Unidos". Pradhan se fue de Nepal en octubre de 2014.

2. 2015: Puente América, Chocó, Colombia

En marzo de 2015, cinco meses después de haber iniciado el viaje, Pradhan se había alojado en Puente América, donde esta alianza encontró su nombre escrito en la pared de madera del refugio improvisado para migrantes.

Para llegar a este punto, Pradhan ya había pagado más de 5 millones de rupias (equivalente a unos 44 000 dólares) a los traficantes. Había cruzado las fronteras de la India, Tailandia, Rusia, España y Brasil y luego viajó por tierra a Bolivia, Perú, Ecuador y Colombia.

Para entonces, la ruta ya se había convertido en camino conocido para los migrantes desesperados que huían del desempleo, la pobreza y la inestabilidad política en Nepal.

Sunil K.C., un joven de 22 años de Kushma, que también atravesó el bosque tupido de Darién y fue deportado de regreso a casa desde Estados Unidos. Hace un año, dijo, había visto un documental sobre la ruta producido por CBS News en YouTube.

Nabin Gurung, un vecino y amigo de Pradhan, tomó el mismo camino en 2018. Cruzar la selva tropical entre Colombia y Panamá fue uno de los puntos más difíciles de su viaje. Le llevó a él y a su grupo ocho días cruzar a pie. A lo largo del camino, vio un cadáver y un hombre de la India con una pierna rota, varados en la selva. Fueron robados por hombres armados.

Gurung recordó vívidamente el agotador viaje a través de la ruta de 50 millas. "La jungla estaba tan mojada que no se podía caminar sin llevar botas de goma. Era tan densa que no pude ver el cielo durante toda una semana", dijo. "Si te enfermabas y no tenías medicinas, tus compañeros de viaje te dejaban morir solo", recordó. "Temíamos la muerte, el arresto y el robo. Subsistíamos con galletas, chocolates y agua". Había llevado un paquete de polvo de cebada tostada llamado Satu en Nepal, que mezcló con agua y bebió para combatir el hambre.

Pradhan, como lo hizo Gurung después de él, había llegado a Panamá en 2015. (En 2019, 243 nepalíes se habían registrado en el puesto fronterizo panameño hasta noviembre, según las estadísticas oficiales). Luego, como nos dijeron sus amigos, continuó a Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala y México. Fue robado en América Central. Fue arrestado en México. Luego, pagó 500 000 rupias adicionales a los traficantes para cruzar a su destino, a donde llegó seis meses después de comenzar su viaje en Nepal.

3. 2020: Nueva Jersey, Estados Unidos

En los primeros años después de llegar a Estados Unidos, Pradhan trabajó en grandes almacenes de cadena en Baltimore, donde fue víctima de un par de robos, según contó su madre. Hace un año, se mudó a Nueva Jersey.

Una mirada a sus mensajes en Facebook e Instagram ofrece un vistazo de cómo es su vida en Estados Unidos. Una foto de portada en Facebook le muestra posando en Nueva York con un rascacielos como telón de fondo. Una búsqueda en su cuenta de Instagram reveló más: haciendo asados y pasando el rato con amigos en la ciudad.

Otro indicio de su vida muestra un comentario de Instagram en una foto publicada el 2 de mayo de 2018: "¡Estás espléndido! ¡Ahora puedes casarte!" En una foto, posa bajo el cerezo en flor. En otra, está pasando el rato con sus amigos. Posando para fotos con ropa de marca y paseando por las playas, Pradhan parece estar viviendo su sueño americano.

No obstante, personas en Kushma dijeron que esas fotos presentaban en gran medida impresiones falsas sobre la vida en Estados Unidos y buscaban alentar a más jóvenes del pueblo a irse de casa. "Puedes monitorear sus vidas en Facebook. Ellos publican fotos de sus viajes a Nepal y sus paseos en Estados Unidos", dijo el trabajador social que ha estudiado la tendencia.

También sostuvo que, por otro lado, la migración ha tenido un impacto positivo en la ciudad. "La mitad de los jóvenes que emigraron ya han recibido tarjetas de residencia. Muchos de ellos han llevado a su familia a allá”, dijo. “Si un miembro de la familia consigue cruzar con éxito la frontera hacia Estados Unidos, la suya es una historia de éxito. La familia construye una casa de cemento y concreto con el dinero (enviado por el migrante)", dijo. "Envían a sus hijos a escuelas privadas donde se enseña en inglés. Compran coches nuevos y se van de vacaciones".

Otros como Binod Pokharel, el dueño de la joyería que intentó emigrar a Estados Unidos, pero fue disuadido por su padre, lo ven de otra manera. "Te lleva tres o cuatro años pagar las deudas contraídas después del viaje. En realidad, son los traficantes y los prestamistas locales los que se han beneficiado de este negocio, no los migrantes", dijo.

De hecho, los miembros de la familia de Pradhan dijeron que todavía debía parte del dinero que usó para llegar a Estados Unidos.

Pradhan había recibido el Estatus de Protección Temporal, que fue otorgado tras el terremoto de 2015 que mató a más de 9 000 personas en Nepal. Después de luchar su caso ante los tribunales de inmigración durante varios años, recientemente recibió una Tarjeta Verde (de residencia), según su amigo Nabin Gurung. "Me dijo que planea visitar Nepal durante Dashain (el festival anual de los hindúes en Nepal, que se celebra en septiembre/octubre)", dijo.

En la casa de Pradhan en Kushma, su madre anhela el día en que la angustiante espera de su hijo termine. "Pasó por muchas dificultades. Él es todo lo que tengo en la vida. Es mi único hijo", dijo. "Me hubiera gustado que se quedara conmigo para mi vejez."

Probablemente el coronavirus no les permitirá reunirse en muchos meses.

*Migrantes de Otro Mundo es una investigación conjunta transfronteriza realizada por el Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), Occrp, Animal Político (México) y los medios regionales mexicanos Chiapas Paralelo y Voz Alterna de la Red Periodistas de a Pie; Univision Noticias (Estados Unidos), Revista Factum (El Salvador); La Voz de Guanacaste (Costa Rica); Profissão Réporter de TV Globo (Brasil); La Prensa (Panamá); Semana (Colombia); El Universo (Ecuador); Efecto Cocuyo (Venezuela); y Anfibia/Cosecha Roja (Argentina), Bellingcat (Reino Unido), The Confluence Media (India), Record Nepal (Nepal), The Museba Project (Camerún). Nos dieron apoyo especial para este proyecto: La Fundación Avina y la Seattle International Foundation.

Regresar

Regresar