En diciembre de 2018, el vietnamita Van Dung Nguyen iba decidido a migrar a Estados Unidos, cuando fue arrestado en el aeropuerto internacional de El Salvador con un pasaporte salvadoreño falso. No lo acusaron de criminal, pero no lo dejaban seguir viaje. Después ya solo quería regresar a casa. Él era tan invisible como los otros miles de migrantes extra-continentales.

Fotografía: Fiscalía General de la República de El Salvador

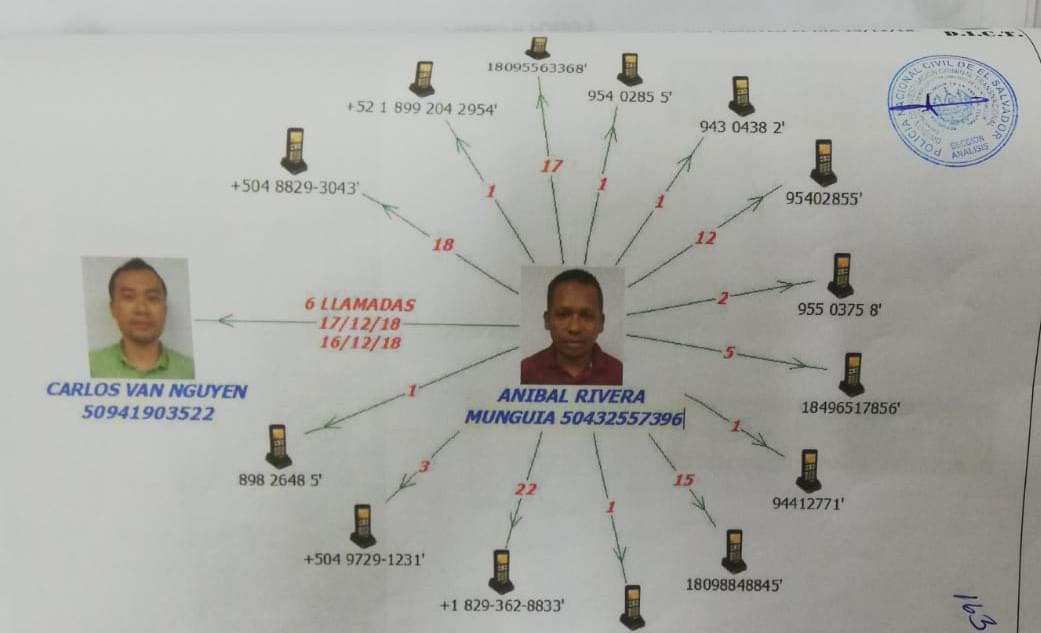

El 19 de diciembre de 2018, el teléfono con código de Honduras +504 32557396 se comunicó vía WhatsApp con el número +509 41903522, con código de Panamá.

Aníbal había intentado comunicarse por tres horas con Nguyen antes de que este por fin le respondiera sus mensajes. Desde las 6 de la mañana de ese día preguntó a Nguyen “Hermano, ¿ya estás en el avión?”, sin recibir respuesta. El vietnamita no tenía acceso a wi-fi.

Cuatro horas después de bajar del vuelo CM 410, de la compañía Copa Airlines, presentó su pasaporte salvadoreño A00620713, bajo nombre de Carlos Van Nguyen, de nacionalidad salvadoreña y con fecha de nacimiento 20 de octubre de 1983. Cuando el oficial de Migración Erick G. pasó el documento por el lector de pasaportes, la máquina activó una alerta de error. Por ello, el oficial llevó el pasaporte y a su propietario a la oficina de la Policía que tiene sede en el Aeropuerto Internacional Óscar Arnulfo Romero, de El Salvador.

Un investigador policial, de apellido Rodríguez, revisó el pasaporte y notó anomalías. Así se lo dijo a su compañero de oficina: que el documento parecía un simple escaneo de un pasaporte real. Rodríguez le preguntó a Nguyen de dónde venía y hacia dónde iba. Nguyen solo contestó con gestos, pero de alguna manera logró explicarles que afuera del edificio del aeropuerto alguien lo esperaba.

Otro investigador policial, de apellido Herrera, acompañó a Nguyen afuera del edificio, donde identificaron a dos personas. Un hondureño, Aníbal Rivera Munguía, y una salvadoreña. El hondureño fue quien aseguró, según la declaración que posteriormente dio el investigador, que él estaba ahí para esperar a un pasajero asiático, y que buscaba llevarlo a la frontera de Entre Ríos, entre San Pedro Sula (Honduras) y Puerto Barrios (Guatemala); a unos 400 kilómetros de ahí.

Del lado hondureño a esta frontera se le conoce como Corinto y está en un área geográfica únicamente compartida por Guatemala y Honduras. El punto salvadoreño más cercano es la frontera de El Poy, aproximadamente a unos 300 kilómetros de la Frontera de Corinto.

Luego de explicar su plan, Rivera Munguía y Nguyen fueron arrestados: el hondureño por tráfico de personas, el asiático por uso de documentos falsos. La salvadoreña no fue detenida e, inexplicablemente, no hay ninguna otra referencia a ella en el proceso judicial. Ni siquiera por qué la dejaron ir.

Ese fue el inicio de una larga cadena de omisiones, decisiones judiciales sin explicación y un extenso espacio muerto para Nguyen, en el que no sucedía absolutamente nada. Ni siquiera le pudieron informar sobre sus derechos tras capturarlo: no había nadie que pudiera traducir para él. Su proceso judicial, que se volvió fofo y pesado; con una indolencia que no es casual para personas como Nguyen, migrantes más invisibles aún que todos los migrantes que a diario escupe: Centroamérica. La revista Factum reconstruyó su historia, como parte de la investigación periodística transfronteriza Migrantes de Otro Mundo, realizada con CLIP, Occrp y otros 16 medios periodísticos.

Los vietnamitas migrantes

La ruta que Nguyen tomó para llegar a El Salvador y viajar de forma irregular no es la que miles de migrantes de Asia y África están recorriendo, en un larguísimo periplo latinoamericano, huyendo de situaciones conflictivas o precarias en sus respectivos países; pero ilustra el rostro más feo de la institucionalidad oficial para atender a los migrantes.

Nguyen viajó desde República Dominicana hacia Panamá. Y de Panamá hacia El Salvador, vía aérea. Desde la primera audiencia en su contra, en el Juzgado de Paz de San Luis Talpa (departamento de La Paz), manifestó, a través de una intérprete, ser de nacionalidad vietnamita, que su nombre real era Van Dung Nguyen y que lo único que quería era regresar a su país de origen, donde tenía familia, dos hijos y se dedicaba a trabajar con estructuras metálicas. Esa audiencia fue el 24 de diciembre de 2018, en la víspera de Navidad. El juez consideró que había indicios para seguirlo procesando y decidió enviarlo a prisión preventiva, a la subdelegación policial de San Pedro Masahuat (La Paz). Las celdas de la subdelegación están diseñadas para albergar a 20 personas, pero en ocasiones han albergando hasta 126 procesados.

Dos días antes, Rivera Munguía también fue enviado al mismo lugar, procesado por tráfico de personas. A él lo había asistido el mismo abogado de oficio que atendió a Nguyen.

Aunque el abogado defendió los intereses del acusado por tráfico dos días antes, su alegato a favor de Nguyen fue que él era víctima de tráfico de personas, tal y como la misma Fiscalía General de la República (FGR) planteaba en su acusación contra Rivera Munguía. La defensa no fue suficiente.

Hasta donde se pudo constatar, Nguyen es el primer migrante de nacionalidad vietnamita oficialmente registrado en los últimos años en El Salvador. De acuerdo a la Dirección General de Migración y Extranjería (DGME) de El Salvador, entre 2011 y 2019 no había sido detenida ninguna persona en situación migratoria irregular de nacionalidad vietnamita. Tampoco por algún delito.

En Guatemala, hacia donde dijo Rivera que se dirigían, el Instituto Guatemalteco de Migración (IGM) tampoco ha registrado migrantes de Vietnam desde 2008. Un panorama ligeramente distinto lo ofrecen las estadísticas de migración irregular de México, la siguiente parada natural en la ruta hacia el norte. Entre 2012 y 2019, la Unidad de Política Migratoria del gobierno mexicano reportó 55 vietnamitas en condición irregular. 26 de ellos únicamente en 2019.

Estados Unidos, el país destino por antonomasia para miles de migrantes irregulares, apenas registra la detención de 411 vietnamitas entre 2007 y 2018 por parte de la Patrulla Fronteriza. Para hacerse una idea, en el mismo período 26 213 ciudadanos de la India fueron detenidos en Estados Unidos.

Millones de vietnamitas están logrando migrar en los últimos años a través de trabajos técnicos, la academia y acceso a estudios superiores, encontró un estudio del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Vietnam de 2012, retomado por la Organización Internacional de Migraciones (OIM).

Sin embargo no todos tienen esas oportunidades. Hay regiones más pobres y con poco empleo, como la provincia de Ha Tinh, al norte del país con costas sobre el Mar del Este, de donde vino Nguyen. De allí también venían los 39 vietnamitas que murieron asfixiados adentro de un camión en Londres en octubre pasado, noticia que le dio la vuelta al mundo. Y también allí las autoridades vietnamitas arrestaron a los sospechosos de tráfico de personas en conexión con el caso de la capital británica.

Pero los juzgados salvadoreños no sabrían eso hasta meses después que Nguyen fue arrestado.

La audiencia que nunca llega

Como Rivera Munguía tenía un proceso en su contra por tráfico de personas, había que tomar la declaración anticipada de su víctima, Nguyen. De esta forma –según dijeron a Factum la Fiscalía salvadoreña y otras fuentes judiciales – podían darle refugio o devolverlo a Vietnam más rápidamente. Pero para poder realizar la audiencia, era obligatorio contar con un intérprete.

La programaron inicialmente para el 13 de febrero de 2019. Pero no conseguían a alguien que pudiera traducirle a Nguyen de vietnamita a español.

La Fiscalía General de la República de El Salvador (FGR) resolvió utilizar a dos intérpretes, uno del vietnamita al inglés; y otro, del inglés al español. La persona designada para interpretar del vietnamita al inglés fue la misma que asistió a Nguyen en la audiencia inicial, la víspera de Navidad.

Lam Vien Cao es una doctora especialista en la enseñanza del inglés que vive en El Salvador desde hace más de diez años y enseña en una escuela privada de estudios superiores. A ella recurrió la FGR, en vista de que el Juzgado de Instrucción de San Luis Talpa, a cargo del caso, que buscó un intérprete del vietnamita al español en la base de datos de la Corte Suprema de Justicia (CSJ), no tuvo éxito.

“Había otras personas además de mí que podían haber interpretado para Nguyen, pero nadie quiso hacerlo”, explicó Cao meses después a Factum. La suya fue una decisión humanitaria. No era la primera vez que interpretaba, ya lo había hecho antes en cortes estadounidenses.

“Es un factor complicado (…) y desafiante”, dijo Cao respecto a lo difícil que es comunicarse para los migrantes extrajeros que no hablan el español.

El expediente judicial muestra y, así lo ratificó Cao (con cuidado de no revelar el secreto sumarial), que aún cuando ella estaba disponible, viajó dos veces en vano hasta el juzgado, pues ni la Fiscalía ni el Juzgado habían conseguido un intérprete de inglés-español.

Cada vez que se fijaba una fecha, la suspendían otra vez porque no coincidían los intérpretes, o las agendas de abogados y fiscales. Siete veces veces pospuso la audiencia el Juzgado de Instrucción de San Luis Talpa, y nada que conseguían garantizarle a Nguyen el derecho a ser escuchado debidamente. A Nguyen lo habían trasladado a la prisión de La Esperanza, conocido como Mariona, desde el 7 de febrero de 2019. La prisión es una de las más grandes y antiguas de El Salvador. A Rivera Munguía también lo trasladaron a esa Mariona.

Tres meses y medio después de esperar paciente encerrado en prisión, el 31 de mayo, Nguyen tuvo su audiencia. Coincidieron todas las agendas, y Cao tradujo del vietnamita al inglés y otra persona, del inglés al español. A las nueve de la mañana empezó a contar su historia.

Había vivido durante los últimos cinco años en Corea del Sur, Vietnam y Haití. No admitió que supiera que el pasaporte que mostró en el aeropuerto fuese falso. Declaró que no se llamaba Carlos, como figuraba en el documento.

Contó que se había tenido que mudar de Haití a República Dominicana porque no le pagaron un trabajo que había hecho en ese país. Después, dijo, le robaron sus documentos y su dinero. Aseguró que personas de una iglesia en República Dominicana lo ayudaron con fondos y el pasaporte salvadoreño. Una vez en Panamá, las autoridades le dijeron que debía viajar a El Salvador porque su pasaporte era de ese país. Dijo que, en realidad, él iba a Panamá para tramitar un pasaporte vietnamita nuevo.

En efecto, en Panamá, a 1400 kilómetros de El Salvador, queda un consulado de Vietnam, un poco más cerca del otro en la región, que está en Ciudad de México. El juzgado instructor envió notificaciones a esas sedes diplomáticas sobre el caso de Nguyen, pero en el expediente no consta documento alguno de respuesta.

Después de contar su historia, y que se la entendieran, como presunta víctima del delito de tráfico humano del que Rivera Munguía estaba señalado como autor, Nguyen ha debido quedar libre.

Además de todo, ese proceso contra el presunto traficante de personas tenía sus propias complicaciones. Cuando la Policía asignó a un perito para sacar la información del teléfono incautado a Rivera Munguía y analizarla, dos semanas después del arresto en el aeropuerto, se descubrió que el laboratorio de la Policía había entregado el aparato equivocado.

La oficina de Migración de El Salvador certificó a la Fiscalía que el pasaporte que usó Nguyen, con datos falsificados - que incluían su fotografía -, había sido reportado como perdido por un hombre, desde mayo de 2016, pero los fiscales no buscaron a su propietario para entrevistarlo.

Aún así, la Fiscalía salvadoreña se empeñó en mantener vivo el otro proceso que le habían abierto a Nguyen por uso de documentos falsos, cuando lo arrestaron hacia cinco meses. La FGR solicitó una certificación de la declaración de Nguyen como víctima, para adjuntarla al proceso en el que lo acusan, y demostrar así que él sabía que su nombre no era el que figuraba en el pasaporte, y por lo tanto, que era un documento fraudulento.

Esto significó que Nguyen tenía que seguir encerrado.

¿Por qué la FGR tomó semejante decisión y procesando como criminal a una víctima de tráfico? ¿Al usar su declaración como víctima, no estaban llevándolo a autoincriminarse? El departamento de comunicaciones no respondió nuestras preguntas y dijo que no podían contestarlas hasta que no pasara la emergencia por la pandemia del Covid-19.

El Juzgado de Instrucción de San Luis Talpa, sin embargo, admitió la declaración como una prueba incriminatoria.

De víctima a victimario

El 8 de agosto de 2019, Nguyen fue enviado a juicio por el delito de uso de documentos falsos. Ese mismo día, el Juzgado de Instrucción de San Luis Talpa decidió sobreseer definitivamente a Rivera Munguía por el delito de tráfico de personas, tomando como base la misma declaración de Nguyen, en la que él aseguró que no había pagado ni un peso a nadie, por el pasaporte falso.

Lo único que detuvo la posibilidad que Rivera Munguía fuera liberado fue la apelación que presentó la Fiscalía salvadoreña. Esta argumentó que al sobreseerlo, el juez no había tomado en cuenta los datos extraídos al teléfono de Rivera Munguía, residente en el departamento Francisco Morazán en Honduras, que lo vinculaban al delito; y que fue decomisado durante su arresto. La Cámara de lo Penal le dio la razón a la FGR y continuó detenido.

¿Qué es lo que no había visto el juez en el análisis de la información del teléfono de Rivera? En el celular aparecían los últimos chats que el hondureño compartió con Nguyen. Intercambiaron fotos e, incluso, un pdf de un boleto aéreo que Rivera Munguía le envió. Tenía además fotografías del documento de identidad original de Nguyen que certifica que es oriundo de Vietnam, nacido en octubre de 1982 y residente en la provincia costera de Ha Tinh.

El sospechoso de tráfico tenía además contactos con códigos telefónicos de México, Panamá, El Salvador y Estados Unidos entre otros. Eso no lo hace culpable, pues puede tener amigos en muchos países, pero en el contexto en que fue arrestado, y el hecho de que el perito policial también recuperó 14 audios en los que “se escucha pláticas referentes al tráfico ilegal de personas”, fortaleció el caso contra Rivera Munguía.

Mientras la apelación de la Fiscalía era tramitada por la Cámara de lo Penal de Zacatecoluca (departamento de La Paz), el juzgado instructor le impuso el uso de brazalete electrónico de monitoreo a Rivera para garantizar que si lo dejaba en libertad no huiría y le pidió una dirección de residencia fija. A diferencia de Nguyen, Rivera Munguía consiguió abogados particulares.

Dos veces las autoridades encargadas de verificar la residencia – que tienen el ampuloso nombre de “Dirección de Monitoreo de Medios de Vigilancia Electrónica” - acudieron a la dirección proporcionada por el acusado en el municipio de Santiago Texacuangos, distante a 17 kilómetros de la capital de El Salvador, San Salvador. En la primera, el 26 de agosto de 2019, uno de los residentes dijo que no conocía a Rivera Munguía. La segunda, el 1º de octubre, el mismo residente les informó que una hija suya buscaba alquilarle un cuarto a Rivera Munguía, pero él no estaba de acuerdo.

Con el tiempo transcurrido – y la apelación fiscal resuelta – Rivera Munguía continuó procesado. Nguyen también. Por bastante tiempo más. Esto a pesar de que El Salvador es firmante, desde décadas atrás, de varios tratados, protocolos y convenciones internacionales que garantizan los derechos humanos.

Uno de los más visibles que podría ser relacionado al caso de Nguyen es el “Protocolo contra el tráfico ilícito de migrantes por tierra, mar y aire” y que es complementario a la Convención de las Naciones Unidas contra la Delincuencia Organizada Trasnacional.

El capítulo 18-12b de dicho Protocolo, que fue ratificado por El Salvador en marzo de 2004, en su artículo 5, establece que: “Los migrantes no estarán sujetos a enjuiciamiento penal con arreglo al presente Protocolo por el hecho de haber sido objeto de alguna de las conductas enunciadas en el artículo 6 del presente Protocolo”. Y en el artículo 6 se detalla, como primera justificación, el haber sido víctima de tráfico ilícito de migrantes. El mismo artículo añade y ahonda como causa no imputable, tener un documento falso que le facilite la migración irregular.

El mismo Código Penal salvadoreño, en su artículo 367-A establece que la mayor responsabilidad recae sobre la persona reconocida como traficante de personas.

Hubo un caso, paradójicamente, muy parecido al de Nguyen, cuyo desenlace fue menos tortuoso para los migrantes. Personas de nacionalidades iraquí y siria ingresaron en 2015 por vía aérea a El Salvador con documentos falsos, que los hacían parecer oriundos de Israel. Su traficante también era extranjero – turco, en ese caso -. Sin embargo, las víctimas, una familia iraquí, otra siria y cinco jóvenes sirios fueron todos enviados a un albergue para migrantes, durante unos tres meses.

Algunos de ellos solicitaron el estatus de refugiado en El Salvador, brindaron su testimonio mientras estaban albergados y posteriormente abandonaron el trámite de refugio.

Con ellos, los fiscales cumplieron los acuerdos de derechos humanos del país: no fueron a ninguna prisión, en un país donde el hacinamiento carcelario sobrepasó desde hace años el 200%.

El turco se llama Sedat Yavas y fue arrestado en 2015, cuatro años antes que Nguyen y Rivera Munguía. Yavas fue procesado y condenado a 8 años de prisión en El Salvador. Como Nguyen, tuvo un proceso judicial extenso y lleno de abruptos por la poca oferta de intérpretes de turco al español. Pero la gran diferencia es que Yavas estaba siendo enjuiciado por tráfico de personas, y no era una víctima del delito, como Nguyen.

Su sentencia en firme llegó hasta dos años después, en 2017. Uno de sus últimos lugares de operación, según detectaron las investigaciones de al menos dos países, fue Brasil.

Para la jefa fiscal de la Unidad de Tráfico y Trata de Personas de El Salvador, Violeta Olivares, el caso de Nguyen podría demostrar que migrantes continúan usando la vía aérea como parte de su ruta clandestina. Pese a tal afirmación, la Fiscalía salvadoreña no parece haber hecho mucho para investigar la hipótesis: en el expediente judicial de Nguyen no figura indagación alguna al respecto ante la oficina de Migración. Tampoco preguntó cómo era posible que un pasaporte nacional reportado como robado tres años atrás, haya aparecido en República Dominicana.

Absuelto, pero atrapado

A inicios de diciembre de 2019, un año después de haber sido arrestado, Nguyen fue absuelto del delito de uso de documentos falsos y enviado al albergue migratorio cuyo nombre oficial es “Centro de Atención Integral para Migrantes” (CAIM), un edificio en una vía de tráfico pesado. Nguyen pasó ahora a depender de las decisiones de las entidades administrativas migratorias.

El CAIM, bajo administración de la Dirección General de Migración y Extranjería, también es el lugar hacia el que son llevados los salvadoreños deportados desde Estados Unidos y México. El 9 de enero de 2020, dos jóvenes salvadoreños en sus veintes, abandonaban con dos bolsas plásticas las instalaciones. Cada martes y jueves, llevan a los deportados salvadoreños hasta allí. Ambos buscaban tomar un autobús hasta el oriente del país, en La Unión, a unas cuatro horas de distancia y seguramente para retomar contactos y volver a salir del país. Una escena repetida hasta la saciedad, frente al pesado portón del CAIM. Lo normal. Lo de cada martes y jueves.

Ese mismo día, personal del CAIM confirmó a Factum que Nguyen continuaba ahí.

De acuerdo al Tribunal de Sentencia de Zacatecoluca, que llevó el caso, Nguyen debía obtener un documento de identidad que estableciera, sin lugar a dudas, que él es vietnamita, para poder ser expulsado del país. Para ello, el trámite debía llevarse a cabo con cualquiera de las representaciones diplomáticas más cercanas a El Salvador: Panamá o México.

El Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y la Dirección General de Migración y Extranjería de El Salvador, cada cual por su lado, negaron las solicitudes de información que hizo este medio sobre el paradero de Nguyen. Ambas entidades alegaron que, al no tratarse de información oficial, no era viable contestar la petición.

La oficina de comunicaciones de Migración también se negó en varias ocasiones a informarnos sobre el proceso de Nguyen.

Semanas antes, la antevíspera de Navidad de 2019, la doctora Cao comentó que se ofreció a continuar como intérprete para Nguyen, para lo que él necesitara mientras se resolviera su expulsión de El Salvador. Los fiscales, sin embargo, no volvieron a contactarla.

Epílogo

19 de marzo de 2020. Desde hace aproximadamente dos semanas, El Salvador declaró una cuarentena nacional debido a la pandemia de Covid-19 y blindó sus fronteras. Fuera del CAIM no hay taxistas ofreciendo transporte rápido para los salvadoreños recién llegados del norte, muchos con décadas de haber abandonado un país que ya no es el suyo. Menos ahora. Un trozo de tierra con nombres desconectados.

El Bulevar Arturo Castellanos, antes atestado de tráfico, ahora está casi desierto.

En el CAIM dicen que no están recibiendo a nadie. Que no están llegando migrantes.

- ¿Y los retornados pendientes que tenían? ¿Tenían a un vietnamita, verdad?

- Ahh, ese se fue como dos semanas antes que declararan la emergencia.

La oficina de comunicaciones de los juzgados salvadoreños informó que Rivera Munguía aún no ha sido enjuiciado; que la audiencia ha sido pospuesta. Que esperarán qué pasa luego de la emergencia. Que esperarán.

*Migrantes de Otro Mundo es una investigación conjunta transfronteriza realizada por el Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), Occrp, Animal Político (México) y los medios regionales mexicanos Chiapas Paralelo y Voz Alterna de la Red Periodistas de a Pie; Univision Noticias (Estados Unidos), Revista Factum (El Salvador); La Voz de Guanacaste (Costa Rica); Profissão Réporter de TV Globo (Brasil); La Prensa (Panamá); Semana (Colombia); El Universo (Ecuador); Efecto Cocuyo (Venezuela); y Anfibia/Cosecha Roja (Argentina), Bellingcat (Reino Unido), The Confluence Media (India), Record Nepal (Nepal), The Museba Project (Camerún). Nos dieron apoyo especial para este proyecto: La Fundación Avina y la Seattle International Foundation.

Regresar

Regresar